Analysis

Antisemitism at German Editors’ Desks

The Algemeiner 23 July 2019

by Remko Leemhuis

An erosion of the post-war consensus on antisemitism in the Federal Republic of Germany is well underway, and Der Spiegel, the leading weekly German news magazine, is not helping.

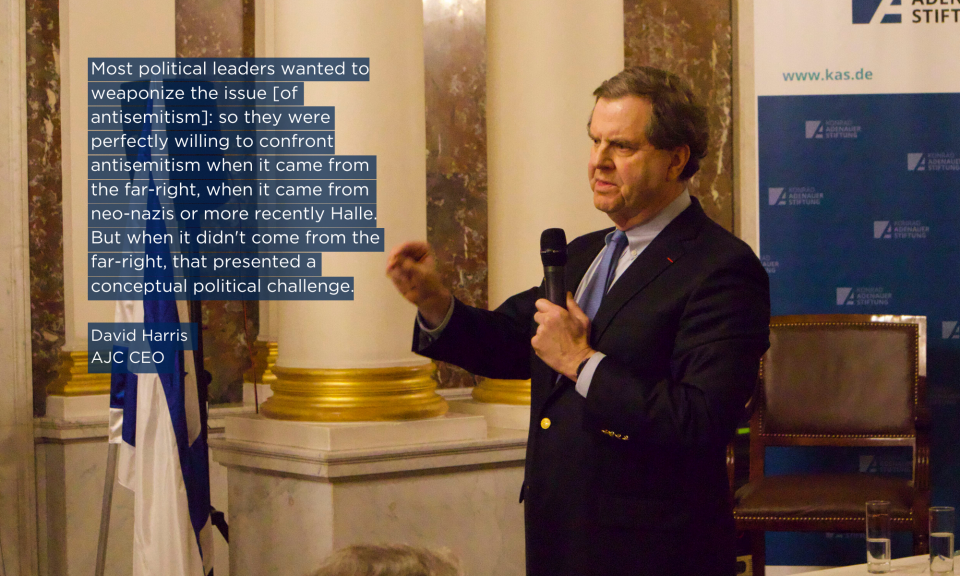

On July 12, Der Spiegel published an article with the headline “Lobbying in the Bundestag: How two organizations control Germany’s Middle East policy,” in both the print edition and SPIEGEL ONLINE. Although the title was subsequently changed, it perfectly reflected the spirit of the article and intent of the six reporters who wrote it, asserting that two small NGOs that combat antisemitism and promote German-Israeli relations control German Middle East policy.

The antisemitic canard that politicians are puppets of secret behind-the-scenes powers is abhorrent and timeless. The allegations of Jewish-Zionist influence in Der Spiegel followed the Bundestag’s clear condemnation of the antisemitic BDS campaign, which seeks the destruction of the Jewish state. The reporters who wrote the article claimed that the rejection of BDS across the political spectrum was due to the sinister influence of the two NGOs, and not because German politicians believe in combating antisemitism in all its forms, including BDS. Der Spiegel‘s message is clear: The Jews buy votes in the Bundestag.

This was not the magazine’s first attack on Jewish and pro-Zionist organizations. In June, in connection with a trip by Green Party Chairwoman Annalena Baerbock to the Middle East, SPIEGEL ONLINE reported, “Baerbock traveled to the Middle East for the first time, not counting a short stay in Israel with the American Jewish Committee, a lobby organization not exactly known for its differentiated views.” The reporter who wrote that piece has not yet responded to our question via Twitter about the basis of this judgement.

Such articles are alarming for both the political culture at Der Spiegel and German society in general. What does it say about a top German publisher when none of the six journalists working on the article, nor any other employee at the magazine, noticed that the piece openly spreads antisemitic ideas? Apparently, when it comes to Israel, Der Spiegel does not apply any journalistic, political, or moral standards.

But then, Der Spiegel‘s coverage of Israel has long been problematic. Headlines and articles regularly portray the Jewish state as aggressive, militaristic, and vengeful. Look at coverage of the second intifada, the 2006 Lebanon war, or clashes with Hamas in 2009 and 2014. Israel is always portrayed as the aggressor, the Palestinians as victims, and any peace initiative as having failed due to stubborn nationalists in Jerusalem.

Headlines regularly appear that do not accurately reflect facts on the ground. If, for example, Hamas attacks Israel from Gaza with rockets and Israel defends itself, then the headline reads: “Israel shoots targets in Gaza — four dead civilians.” Such headlines are unfortunately widespread in mainstream European reporting on the Middle East.

What more does it say about Germany’s largest political magazine that no one could believe German politicians fight antisemitism and strive for good relations with the Jewish state out of a genuine political and historical conviction? Just as problematic is the insinuation that some parliamentarians did not oppose the BDS resolution out of fear of being labeled antisemitic. The argument that one is not allowed to criticize Israel is simply another classic antisemitic trope. The authors should read their own magazine for an example on how “criticism” of the Jewish state is done often and regularly without any repercussions.

After the article was published, the authors and the magazine’s editors faced heavy criticism. This reaction is undoubtedly a good sign. Nevertheless, as far as the political culture in Germany is concerned, the fact that such an obviously antisemitic piece can be published at all is deeply troubling. Will the outcry be as strong when similar articles are published?

We know from historical experience that antisemitism does not poison society overnight. It is a process. But with every breach of taboos, the limits of accepted discourse are furthered.

According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, nearly half of all young European Jews have experienced antisemitism firsthand. So the next time someone asks how such a thing could happen in Europe in 2019, they should also take a look at the arsonists at the desks of editorial offices. Writing and ideas have consequences — consequences that the Jews in Berlin, Paris, and other European cities feel daily.