Analysis

To Honor the Burgas Victims, Condemn Hezbollah

By Daniel Schwammenthal

The Wall Street Journal Europe

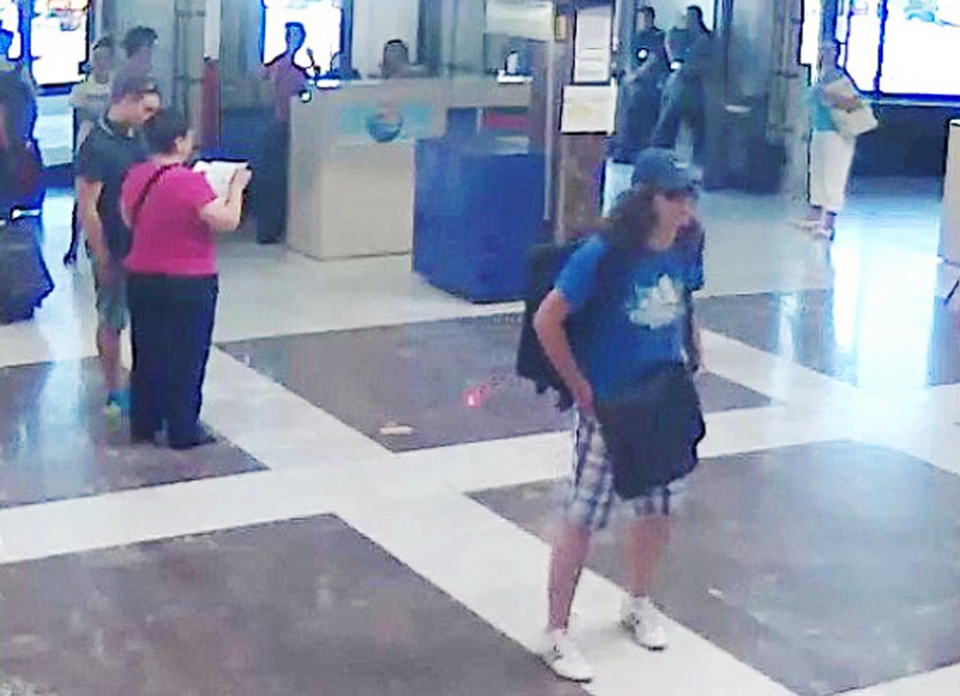

The tourists had just boarded the airport bus in Burgas, Bulgaria, when the bomb exploded. The blast was so strong that it blew off the roof. Flesh, blood and body parts were everywhere. Five of the six victims were Israeli four were in their 20s. Kochava Shriki, 44, had learned that very day that she was finally pregnant after years of trying. Mustafa Kyosov, the 36-year-old Bulgarian bus driver, was also killed.

Behind the statistic that 32 people were injured in the attack—including an 11-year-old child and two pregnant women—lies the horrific reality of severed limbs and severe burns that will haunt many of these victims for the rest of their lives. Thursday marks one year since the bombing, yet this sad anniversary will pass without any EU response.

The Bulgarian government's investigation clearly points to Hezbollah, and a Cypriot court in March convicted a confessed Hezbollah member of preparing similar attacks in Cyprus. Yet Brussels has so far failed to confront the global terror group. In fact, the EU has for years resisted calls to designate Hezbollah as a terrorist organization at all. Its arguments—that there is not sufficient evidence to do so, that such a move would "destabilize" Lebanon—rang hollow even before the events in Bulgaria and Cyprus. Hezbollah has a long history of terror.

The EU criteria for adding an organization to its terrorist list are actually very easy to meet. All that is required is for a "competent authority" to initiate an investigation. You don't even need an indictment, let alone a conviction. Now that Cypriot authorities have convicted a Hezbollah member, a terrorist designation should easily withstand any possible judicial challenge. As for concerns about Lebanese stability, Hezbollah has practically carved out an independent state within Lebanon.

It fields a more powerful militia than the country's official army, which Hezbollah also controls to a large extent. The idea, therefore, of Hezbollah as a stabilizing factor in Lebanon always sounded as convincing as the notion that the Mafia is a stabilizing force in Italy. And now that Hezbollah's brutal military intervention in neighboring Syria has raised the specter of the civil war spilling over into Lebanon, even the most cynical understanding of the concept of "stability" can no longer justify Europe's kid-glove approach toward Hezbollah. EU resistance seems to be waning.

There is cautious optimism that when foreign ministers meet on Monday, they will agree to designate Hezbollah's military arm, at least, as a terrorist organization. True, trying to distinguish between a political and military arm is a distinction without a difference—one that even Hezbollah itself rejects. There is only one Hezbollah, with one unified command structure. By listing only the military arm, the EU would probably not be able to use many of its antiterror instruments against the so-called "Party of God," such as seizing Hezbollah's assets or putting a stop to its fundraising in Europe.

The group currently raises cash on the Continent under the guise of its purported social-assistance projects. But even though such a designation would be largely symbolic, the power of this symbolism should not be underestimated. Such a decision would be the first official EU recognition of Hezbollah's true nature. It would be another blow to the organization's image, already suffering due to its support for Bashar Assad's scorched-earth policy, which is even criticized within the Lebanese Shia community.

It is precisely because Hezbollah also strives to use politics to advance its extremist ideology that it is vulnerable to public naming and shaming. Listing Hezbollah as a terrorist organization is probably also the best thing the EU could do to stabilize Lebanon, not destabilize it. The designation would serve as a warning to the group to tread more carefully in the future—both in Lebanon and in Syria. It would also be a welcome first step for European leaders to meet their obligation to their own people: to protect them from terrorism.

Inaction would be a dangerous sign of weakness and only invite more Hezbollah attacks. Monday's meeting of the EU Foreign Affairs Council could be Europe's best and possibly last chance to start getting its Hezbollah policy right. If the 28 foreign ministers fail to reach consensus, the danger is that the designation may never happen.

The ministers' next meeting is scheduled for October, after Europe's long summer break. By then the momentum for listing Hezbollah as a terrorist organization may have fizzled out. EU governments already missed their opportunity to take a stand before the one-year anniversary of the Burgas attack. They must not waste the chance to correct their mistake by telling Hezbollah that it cannot get away with murder.

Mr. Schwammenthal is director of the AJC Transatlantic Institute in Brussels.