Analysis

The Road to Arab-Israel Peace No Longer Runs Through Ramallah

14 September 2020

Avi Mayer

For decades, the consensus among senior diplomats, Middle East scholars and the international foreign policy establishment has been that resolving the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is the key to broader Arab-Israeli peace.

As Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the United Arab Emirates and Foreign Minister Abdullatif Al Zayani of Bahrain travel to Washington ahead of Tuesday's historic signing ceremony for peace agreements between Israel and the two Arab Gulf states, it is evident that the prevailing wisdom is crumbling before our eyes and a new Middle Eastern peace doctrine is rising to take its place.

On May 15, 1948, the seven founding member states of the Arab League launched what the body's then-secretary general, Azzam Pasha, called a "war of extermination and a momentous massacre" against Israel, which had been established the previous day. Following Israel's resounding victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, the League gathered in Khartoum and issued its notorious "three 'no's": "no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with it." In 1979, the Arab League responded to the Camp David Accord between Egypt and Israel—the first step by any Arab country toward peace with the Jewish state—by bitterly condemning Egypt, calling on member states to sever ties with the country, relocating its headquarters from Cairo to Tunis and suspending Egypt's membership in the pan-Arab organization for nearly a decade.

In the half-century since they were first formulated, the "three no"s have gradually been replaced by a cautious "maybe."

In 2002, the Arab League endorsed what has come to be known as the Arab Peace Initiative, predicating peace and diplomatic relations with Israel on the Jewish state's full withdrawal from "the occupied Arab territories" and its acceptance of a Palestinian state on the entire West Bank and Gaza Strip, with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Though hailed as a historic move, the initiative cemented the prevailing dogma that peace between Israel and the Arab world is possible—but only once Israel settles its conflict with the Palestinians. For decades, that has been the refrain from Western, Arab and even some Israeli diplomats: first peace with the Palestinians, then with the rest of the Arab world. Or, as one former senior U.S. official memorably put it, "the road from Jerusalem to Riyadh runs through Ramallah."

On Wednesday, the Arab League took a step down a new road.

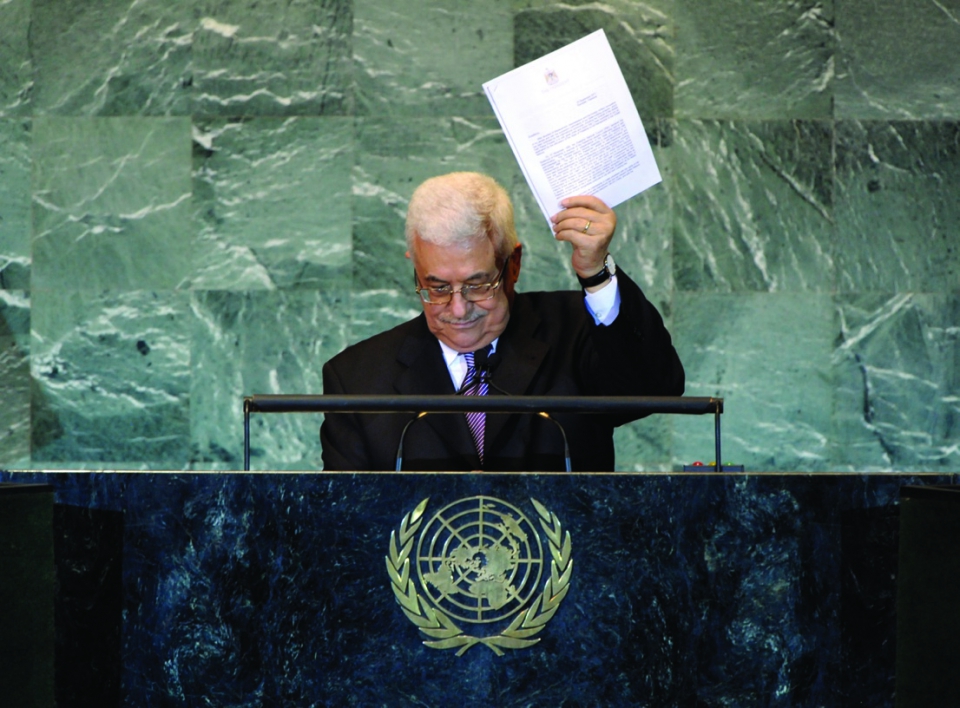

Several weeks after turning down Palestinian calls for an emergency session upon the announcement of the recent peace agreement between the United Arab Emirates and Israel, Arab League foreign ministers gathered virtually for a prescheduled meeting in which a resolution condemning the move was to be considered. The Palestinian foreign minister, Riyad al-Maliki—long accustomed to unqualified public Arab support—opened the gathering by insisting on a full-throated condemnation of the Emirati-Israeli deal. "This meeting must release a decision rejecting this step," he said. "Otherwise, we will be seen as giving it our blessing, conspiring with it or attempting to cover it up."

His demand fell on deaf ears.

After three hours of debate, the Arab ministers refused to endorse the Palestinian-sponsored resolution, with Arab League officials publicly blaming the Palestinians' intransigence for the motion's failure. The body's leadership did issue a condemnation—not of the UAE's peace agreement with Israel, but rather of "bullying and hostility" by Iran and Turkey, both of which have angrily opposed the Emirati-Israeli deal and threatened to punish the UAE. Commenting on the matter, Arab League Secretary-General Ahmed Aboul Gheit reaffirmed the right of member states to pursue independent foreign policies. "Every sovereign state has the indisputable right to conduct its foreign policy in the way it wants, and this is something that this council [Arab League] respects and endorses," he said.

The Palestinians responded furiously. "First we thought that the United Arab Emirates was the only country that had stabbed us in the back," one senior Palestinian official said. "On Wednesday, we saw how several other Arab countries have betrayed the Palestinian people and the Palestinian issue." "Arab brothers have abandoned the Palestinian issue," said another Palestinian official; "this is a thunderous collapse," said a third. The Palestine Liberation Organization's Executive Committee called the Arab League's failure to condemn the UAE "extremely dangerous."

Indeed, Palestinian leaders would do well to view Wednesday's events in a cautionary light.

Across the Middle East, Arab governments are gradually pursuing foreign policies that, while mindful of Palestinian concerns, refuse to subordinate their national interests to Palestinian demands. Driven by common threats—most notably, a belligerent and fundamentalist Iran—and shared economic opportunities, Arab officials are showing an openness to Israel that has seldom, if ever, been seen before. Fed up with a recalcitrant Palestinian leadership, Arab leaders are moving on, declaring support for the Palestinians while fostering ever closer ties with Israel. As Dubai's vocal deputy police chief, Dhahi Khalfan Tamim, recently tweeted to his 2.8 million followers, "Rid yourselves of this notion that you don't build relations with Israel except at the command of [Palestinian Authority President] Mahmoud Abbas."

Private jets carrying Israeli officials are landing in ever more Arab capitals, and Arab governments are increasingly opening their countries' doors to Israeli tourists and businesspeople. Last week, Abu Dhabi instructed hotels to start offering kosher food in preparation for an anticipated influx of Jewish visitors. Saudi Arabia announced that it will permit commercial flights to and from Israel to pass through its airspace, easing tourism and trade. Speculation about which Arab country will be the next to normalize its relations with Israel is fierce.

To be sure, the dissipation of antiquated thinking does not obviate the need to resolve the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. For reasons of security, morality and demography, among others, Israel must continue to pursue a peaceful settlement of its most intimate geopolitical conflict, which threatens to undermine Israel's future as a Jewish and democratic state. It is also likely that Arab countries will ask Israel to make gestures to the Palestinians as part of the normalization process, as the UAE did in securing Israel's commitment to suspend the application of Israeli sovereignty to parts of the West Bank.

But Israel can only pursue true peace with a Palestinian partner willing and able to make the painful compromises that will be necessary to bring about a lasting solution. Such a partner has proven elusive, as successive Palestinian leaders have dragged their feet, secure in the knowledge that the Arab world wouldn't dare make peace with Israel without them.

Tuesday's White House ceremony should serve as a wake-up call to Palestinians who have long been led to believe that Arab leaders will sacrifice their own national interests on the altar of Palestinian rejectionism. That is clearly no longer the case. As Palestinian diplomat Husam Zomlot complained to The New York Times, the UAE-Israel peace deal "takes away one of the key incentives for Israel to end its occupation—normalization with the Arab world."

Put differently, the road to Arab-Israeli peace no longer runs through Ramallah.