Analysis

France’s Hezbollah Problem

Le Point - Initially Published in the Miami Herald

27 September 2020

Simone Rodan-Benzaquen and Anne-Sophie Sebban-Bécache

Lebanon’s future is at stake, and its oldest European ally, France, holds the key to making a difference. To his credit, President Emmanuel Macron has invested considerable time and effort since the Aug. 4 explosion at Beirut’s port left almost 200 dead and thousands injured.

After Macron’s second visit to Beirut, on Sept. 1, Lebanese political forces agreed on a two-week deadline to form a mission government, as a prerequisite for the international bailout France is spearheading.

The deadline passed as the same actors continue to play the same game to block any kind of change. Indeed, Hezbollah and its Shiite ally Amal have, according to reports, insisted on getting the Ministry of Finance and other vital ministries.

By considering Hezbollah as a legitimate interlocutor in the process — engaging its representatives in Lebanon — France is perpetuating the problems. Unless Macron addresses the issue of Hezbollah, nothing will change.

The Iranian-backed terrorist organization has held a grip on Lebanese society for decades. Contrary to what French diplomats have asserted, the organization is not a legitimate political actor. It has used violence and intimidation to gain political power during the past two decades. As a case in point, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon recently convicted a leading Hezbollah operative in the 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

It is using the same methods of intimidation today to push back any profound changes that could affect its dominant position in the country.

But many within Lebanese civil society have become more outspoken, refusing to give into Hezbollah’s blackmail. Significantly, more voices have openly condemned Hezbollah, even hanging Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in effigy.

Hezbollah not only is the worst enemy of the Lebanese political and societal system. It is a major security threat. A non-state within a state and has an estimated 120,000 missiles, Hezbollah has become the world’s best-equipped terror group, better equipped than the Lebanese army itself.

U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently called again for “the disarmament of all armed groups in Lebanon so that there will be no weapons or authority in Lebanon other than those of the Lebanese state.”

On its own initiative and on behalf of the Iranian regime, Hezbollah makes regular incursions across the Israeli border and intervened early in the nine-year-old war in Syria in support of President Bashar al-Assad, accused of crimes against humanity.

Lebanon’s rebirth can’t happen if its government is stripped of legitimate use of force.

France and, more broadly, Europe and the international community must urge Hezbollah’s immediate disarmament.

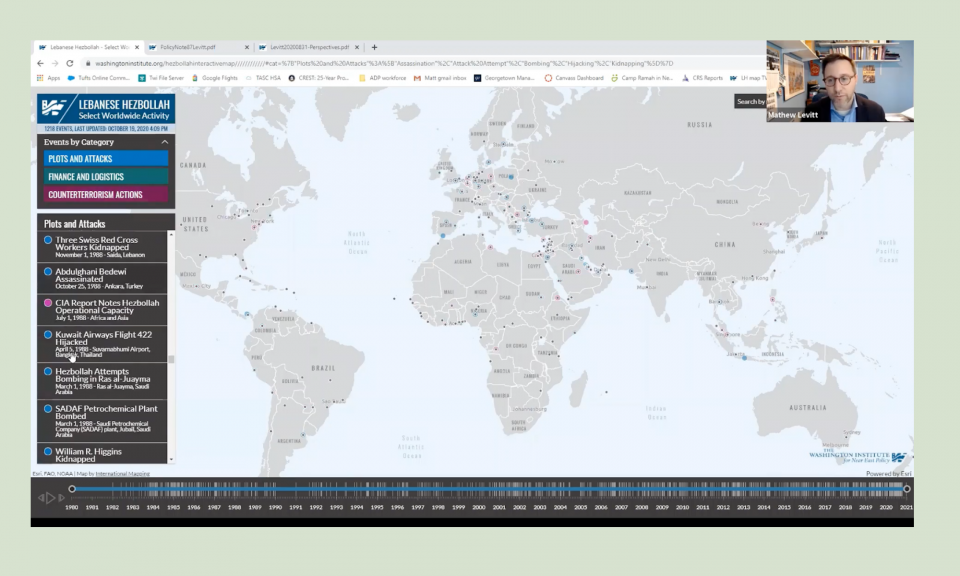

Hezbollah is not just a threat to the Middle East. For many years its activists and supporters have raised money, stored weapons, and engaged in money-laundering, counterfeiting and narco-trafficking networks. Ammonium-nitrate depots have been found both in Southern Germany and in the outskirts of London. And on Sept 17, Ambassador Nathan Sales, U.S. State Department coordinator for counterterrorism, revealed to the American Jewish Committee (AJC) that significant caches of ammonium nitrate moved through Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. He said believed that this malicious activity was still underway.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Hezbollah carried out several terrorist attacks in Paris and London. The Burgas airport attack in 2012 and the arrest of a Hezbollah operative in Cyprus who had been surveilling sites for a possible terrorist attack, led the European Union to declare the “military” wing of Hezbollah a terrorist organization. But that European invention of a bifurcated Hezbollah has had no effect.

In reality, there is only one Hezbollah. Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and, most recently, Lithuania have recognized that truth. Without recognizing it as well, without sanctioning Hezbollah’s responsibility in today’s failure to exit the crisis, France’s efforts will fail.

During his Sept. 1 visit to Lebanon, Macron, citing Italian Marxist writer Antonio Gramsci, said that, “The new is having a hard time emerging, and the old is persevering. We must find a way through.”

Finding a way through will be crucial. The path will be long and complicated. It will require a concerted effort from the international community, which France is leading. Paris is scheduled to host an international conference on Lebanon on Oct. 15. If France does not want to be responsible for giving birth to a “new-old” Lebanon, addressing the central issue of Hezbollah is essential.